Cracks

- Aditya Suresh

- Jan 3

- 7 min read

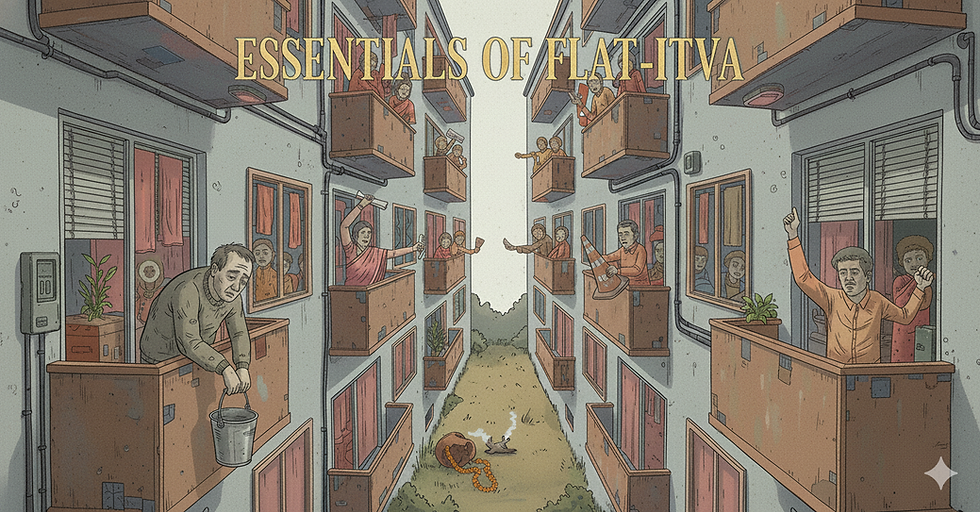

Mr. Jana was cleaning my apartment the week he was fired. He and I, we used to have small chats whenever he came there to clean, which was usually once a week. That was probably because I spoke manageable Hindi, enough to be at par with his cocktail of Bengali and Hindi — which probably was more than what most people he worked with could do. After his first day of work and what was expected of him was well established, he would walk in quietly upon being let in, open the balconies, and roll up his clean pants and shirt that made him look more like a chauffeur than a cleaner.

“Balcony first,” he would announce, and take around three hours to clean each nook and cranny of a somewhat small apartment.

After talking more, I discovered that Mr. Jana was from Kolkata and had a son working in Bangalore. I had a clichéd talk with him about Satyajit Ray movies, at the end of which Mr. Jana just said, “Those are very old movies. I don’t get time to watch a lot of new movies.” Mr. Jana probably found me a decent enough person to share his wage worries. He explained the story about how he used to work for the building’s construction company for 800 rupees a day and now he earned 650 rupees a day cleaning the building and the builder’s office next door. He took great pride in explaining that the General Manager was only happy with Mr. Jana’s cleaning expertise and that he was urging Mr. Jana to stay there and promised him a hike to 800 rupees a day. Mr. Jana, after a couple of months, grimly said there was no progress once I enquired about it.

“I don’t see the point of staying so far away from home. I have to spend half of what I earn to live here. They said they will introduce me to other people in the flat who may need cleaning services, but Mr. Satish, the caretaker, always just says that he will look into it.”

Mr. Jana’s dejected look made it evident that Satish never really “looked into it.” I promised Mr. Jana that I would recommend him if I came to know about someone looking for a cleaner. Mr. Jana looked hopeful. Two days later, Mr. Jana was dismissed for asking for the hike.

I called Mr. Jana to ask him whether he would be able to come that Sunday to clean, being in the dark about the whole thing. He filled me in. I asked him whether he could still come, because it’s my home and I don’t need him to be working in the company to work at my house. Mr. Jana gladly agreed, finished his work, and left. Then came the morning of the “Tribunal.”

I was summoned to the management office. Satish sat behind a desk that was too big for him, nervously adjusting a tie that looked like it had been tied by his boss. He was a man who lived in permanent fear of the General Manager, and that fear manifested as a strange, twitchy aggression toward everyone else.

“We saw the log, sir,” Satish said, his voice high-pitched and defensive. “You let Mr. Jana into your flat yesterday. After he was terminated by the Boss.”

“He needed the work, Satish,” I said, trying to keep my voice steady. “The flat was dirty, and I don’t see how Mr. Jana working in my flat is a problem.”

“It’s not about that!” Satish hissed, leaning forward. “The Boss is furious. If one laborer starts demanding ‘fixed increments,’ the whole system collapses. Also, Jana knows how the building runs — he knows where everything is. By letting him in, you’ve created a security breach.”

“Security?” I laughed, though it felt thin. “He has a mop and a bucket.”

Satish pulled out a tablet, swiping frantically to a CCTV feed. “Look! Here he is at the service entrance. He’s not on the rolls anymore, yet he’s walking the halls. He knows the service codes. He knows where the cameras don’t reach. To the Boss, an ex-employee who refuses to stay away is a threat to the compound’s safety. He’s ‘unaccounted for.’ If a pipe bursts or a wire is cut, who do we blame? The General Manager is not happy about you calling him, and I think the residents association would agree. The man thinks he’s owed more money!”

“He’s not a saboteur, Satish. He’s a grandfather from Kolkata.”

I looked at Satish — this small, terrified man who was willing to destroy a cleaner’s life, citing cracks in security, just to please his master. Then I thought about the master — the General Manager — and the cracks in his ego that prompted him to pick a fight with someone whose lifetime earnings couldn’t match his month’s earnings. I felt a cold knot of anxiety in my stomach. I lived here. I needed my car permit renewed. I didn’t want the association’s ‘security team’ making my life difficult. I guess there were cracks in my humanity after all.

“I… I didn’t think of it that way,” I murmured, the betrayal sliding out of my mouth. “I thought he was just finishing his week. I won’t call him again.”

“Good,” Satish said, visibly relaxing. “Because the Boss wants him banned. He’s told the gate guards that if Jana is seen within fifty meters of the gate, it’s a ‘Code Red.’ We’ve told the police he’s been loitering with intent.”

When I left the office, I saw Mr. Jana by the service lift. He had his sleeves rolled up, clutching his bag of cleaning supplies, waiting for a lift that never seemed to come for people like him. He saw me and gave a small, dignified nod. He thought we were still on the same side because of our “small chats.” Mr. Jana timidly reminded me about helping him find more work like I had promised.

“I will look into it for sure, Mr. Jana,” I lied, disgusted with myself.

An hour later, I watched from my balcony — the one he had made spotless — as Bahadur, the watchman, led him to the gate. Bahadur looked like he wanted to be anywhere else, but Satish was watching from the office window, clipboard in hand.

At the gate, Mr. Jana stopped. He looked up at my balcony one last time. I stepped back into the shadows of my living room, hidden. He adjusted his bag, his back straight, looking more like a chauffeur than a man who had just been branded a criminal for wanting 150 rupees more. He walked toward the main road, merging into the grey smog of the city.

I sat down in my clean, quiet apartment, listening to the silence, and realized that the “security” Satish had promised felt exactly like a prison.

A week later, Satish sent the replacement. He messaged me on WhatsApp with a flurry of thumbs-up emojis:

“Sir, providing top-class premium cleaning at 30% lower cost. The Boss has approved. Security verified.”

His name was Mr. Ranjan.

He didn’t walk in like a chauffeur. He walked in like a man who had been told he was lucky to exist. He didn’t roll up his sleeves with the quiet precision of Mr. Jana; he kept his head down, clutching a plastic bucket that was already cracked.

“Balcony?” I asked, trying to find the old rhythm.

“Yes, sahib,” he muttered, his Hindi thick with an accent I couldn’t quite place. He worked for two hours. He didn’t move the flower pots to scrub the rings of mud beneath them. He didn’t reach for the cobwebs in the high corners of the ceiling. He just wiped a wet, grey cloth over the center of the floor, leaving streaks that caught the afternoon light like scars.

I stood in the doorway, a hot, petty anger bubbling in my chest. I wanted to tell him that Mr. Jana used a specific brush for the tile. I wanted to tell him that his “premium cleaning” was a joke — a mess, a slap in the face to the man who actually did his job well.

“You missed the corner,” I said, my voice sharper than I intended.

Mr. Ranjan stopped. He straightened up slowly, rubbing a hand over his lower back. He looked at the corner, then at me. His eyes weren’t defiant; they were just exhausted — the same eyes Mr. Jana had.

He dipped his cloth back into the dirty water. “Sorry, Sahib. I have two more flats to finish before four o’clock. Satish-ji said if I don’t finish five flats a day, I won’t get the daily rate.”

The anger in my chest died instantly, replaced by a cold, heavy shame. The pavement I overlooked from the ninth-floor balcony looked strangely welcoming.

Mr. Ranjan was another Mr. Jana, just a few months older and a few degrees more desperate.

When he finished, I handed him a cup of tea, which surprised him.

“Thank you, sahib,” he said, wiping his mouth with his sleeve. He picked up his cracked bucket and headed for the door, scurrying out before Satish could see him “loitering” in my presence.

I walked out to the balcony. The floor was damp, but the grime in the corners was still there, tucked away where it was easy to ignore. I chose to ignore it – it seems I’m pretty good at ignoring things, even important ones. I looked down at the street. I could see Satish standing by the main gate, checking his clipboard, looking like a Lilliputian king.

I looked at the streaks on the floor. I thought about Mr. Jana’s son in Bangalore and Mr. Ranjan’s five flats a day. The apartment was “secure.” The Boss was happy. The “Security Threat” had been neutralized. I hoped, with a quiet sort of disgust, that Mr. Jana and Mr. Ranjan and their worries would simply fall through the cracks of my memory—after all, they were already people who had fallen through the cracks of the world’s concern.

I went inside and closed the balcony door and tried to dirty the glass on purpose. But no matter how much I tried, I couldn’t stop seeing my own reflection — the scared, useless man who watched it all happen but did nothing at all over the fear of losing pool privileges.

Comments